Let’s start in Brighton, in Britain. Early 1990’s

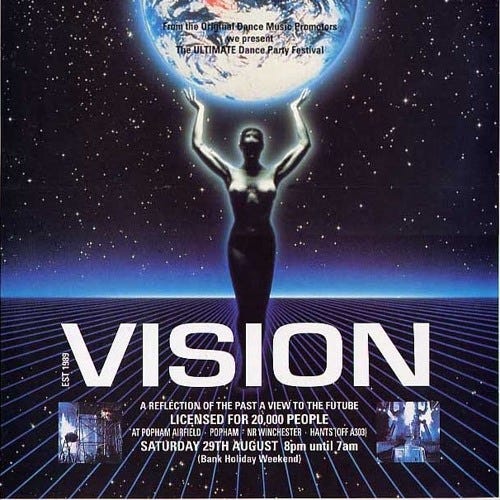

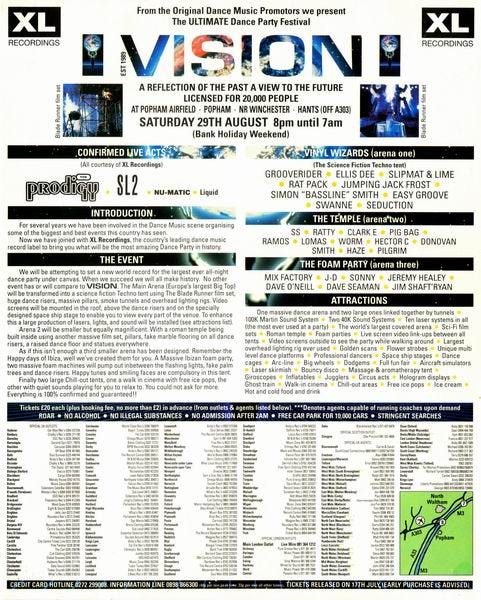

I grew up raving across the south coast from Slinky and the Manor in Bournemouth to Sterns and the many fields around the M25.

Many weekends we would hang out in Brighton, a visit to Infinity foods, the original UK whole foods store (think brown rice, and and bulk lentils in brown bins), grab materials for my parent’s side businesses, and I would get lost in all the record and comic shops - big up the Lanes.

There’s something about seaside towns that always feels just a little bit weird. Maybe it’s the combination of British Victorians disguising early city breaks as health trips, maybe it’s the fact they all feel a little worn down, like a moldy 70’s Vegas, in the rain. Like the ghosts of funfairs echoing off pebbles and piers. It was into this slightly feral liminal space that Big Beat was born, cheap lager, breakbeats, and bootleg funk. A culture that smelled of poppers, speed, and speakers blown out at the Concorde.

Fast forward to London, 1996, I had left the south coast behind, spent a few years in Liverpool, mainly at Cream and Garlands, and was now working in London. My introduction to London nightlife was a mix of the Gardening Club, the Cross, Club UK, and Ministry of Sound. By now, I was tired of the scene, ecstasy was getting so strong it could kill a moose, and I needed something new.

I had been spending more and more time at the Blue Note, the 333, I had a new job, I was running with a new North London crew, I had moved to Stoke Newington, I was off the pills, and looking for something different.

I still remember the first time I heard a Skint 12".

It had a hip-hop feel in that very British way, concrete carparks, tags, UK graffiti, cheeky samples, and it was loud, it felt like it might set fire to the stylus. The Islington pubs were the place to be at this point, Sara Cox, and Kate Moss, “Ladettes” with short hair, combat trousers, pints instead of pills, and then out of all of that, Big-Beat came along.

A genre wearing crappy cheap sunglasses indoors, mashing punk and hip-hop into house music’s skin, and running riot through late '90s clubland. Influenced by hip hop, acid house, funk, and punk energy, Big Beat was a sample-happy riot of breakbeats, low-end filth, and absurdity. It was rebellious and silly in equal measure. And Skint Records was its nucleus.

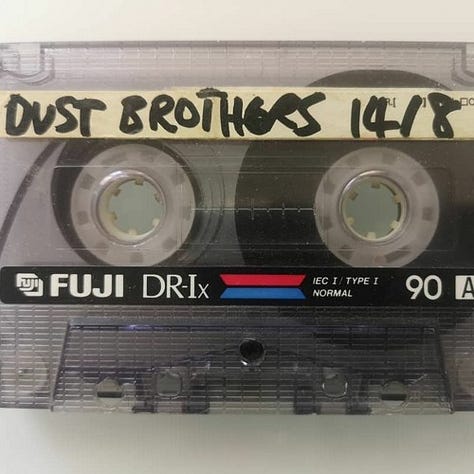

Skint became synonymous with playful nihilism and rave nonsense. Releases from Fatboy Slim (aka Norman Cook), Bentley Rhythm Ace, and Lo-Fidelity Allstars rattled crappy pub soundsytems all across N1. It brought light to some absolute nutters, Jon Carter, whose nights with Monkey Mafia married dub and absolute carnage, Justin Robertson, Wall of Sound, and FC Kahuna, always with their Hawaiian shirts and the dirtiest funk samples. The Heavenly Social — an iconic London basement at the Albany pub, the Big Beat’s temple. I got to see Daft Punk play pre-robot helmets. Saturday nights with the Chemical Brothers (then still Dust Brothers), Justin Robertson, and residents like Damian Harris himself turned up the scene. Nights at the Big Kahuna Burger with Derek Delarge had that timely Tarantino-esque Pulp Fiction humor and cult status. It was more about energy in a tiny space and the sweat than anything particularly tasteful. The tracks felt architectural. Brutalist of course. Built from poured concrete, softened by shitty Briitsh rain. Beats smeared and echoing, bouncing off the walls of an abandoned swimming pool. Big Beat made sense of a post-Nirvana, post-rave, post-handbag house, pre-Garage, pre-burial world.

Skint was never supposed to be the main act. It was the “annoying little brother” to the more respectable Loaded Records, which was releasing proper house music. Damien Harris co-founded the label back in 1995. He used Skint to sneak out weird B-sides, edits, and breakbeats. Early on, the label was full of mad energy, like a basement full of samplers left on overnight. There was a real pub science to it all: low-bit loops stretched across Akai samplers, tape hiss left intact, acid lines riding just behind the beat. Damian wasn’t chasing perfection. He just wanted to break your neck.

“I always liked music that created space around you...

Dub taught me that what isn’t there can hit just as hard.”

Damian Harris

Damian’s journey began way back in Brighton with skateboards and stolen Mo’Wax records. A graphic designer by trade, he found himself deep in the early ‘90s London scene — somewhere between record shops, Soho dives, and gallery spaces.

“I did a fine art course called Alternative Practice.”

His degree show was nine record players in a room, deliberately stuck on the run-out groove, incredibly loud. “My dad came, thought the records had finished, and put them back to the beginning. ”

Damian Harris

But, like all things loud, Big Beat burned out. The formulas got tired. Major labels tried to cash in and missed the point. Skint got bought, but by then it was pretty much over. The early 2000s ushered in more minimal sounds, Microhouse, then Dubstep. And for a while, Big Beat became a joke. Adidas tracksuits, cheeky sample packs, nosebleed energy. Damian has always been more curious than a careerist music mogul, quietly at the heart of things, letting the Cook’s and Lavelle’s take the limelight.

He never totally disappeared. He pivoted. Adapted. Evolved. Years later, as we all grew old, I rediscovered what he had been doing. He took a long break from the scene, worked on film and commercial projects. Spent time in Berlin. Watched the music landscape change. And when he came back, it wasn’t to recreate Skint. It was something gentler. More reflective. A little strange. A little psychedelic. It was Vicious Charm.

Vicious Charm started quietly. No big press push. Just a string of beautiful, dubby, haunted albums. Where Skint was like a bomb going off in basements across London, Vicious Charm was someone at sunset, enjoying a spliff walking sitting under a tree in a field, without any cares. In many ways, the label feels like Damian’s way of reclaiming space. Releasing acoustic albums, with real singing, guitars, more Van Morrison than Van Damme. And what has always pulled me in has been his Generalisation dubs, his remixes on each album.

He’s always talked about how remix culture shaped him, and with Vicious Charm, the Generalisation Dubs continue that journey. Harris began requesting that he do a “Generalisation Dub” for every release. It's his way of gently guiding artists into a deeper space. Slower tempo. Less clutter. More smoke. Instead of asking other people to do remixes for the “collab factor”, he makes his own. I swear he makes it part of the contract. Reworking releases into long, dubbed-out echoes, looping phrases into mantras. A spiritual reinterpretation. A version of the track you might hear at 6 AM on Devils Dyke. Or through a fogged-up car stereo coming home . It’s more than just a sound. Strip the track down to its bones, then let the bones breathe.

Take Jim’s Still River Flow. The original is already meditative, full of long tones, dusty drones, and dub percussion. But on his Generalisation Dub, Harris stretches it way further. healing music. Late night. Incense lit. The kind of track I would play at the very end of a set, when no one wants to leave.

Or listen to Velodrome, by Chris Coco. It begins like waking up in a cave made of quartz. Frequencies. Textures. The dub here isn’t just production. It’s a philosophy, subtraction, echo, and space.

If Skint was a punch to the gut from your mate, Vicious Charm is the hair stroke recovery. It speaks to a wider shift. Dance music’s gotten older. We all got old. We need spaces to come down. To feel frequencies in a room without needing to dance. Harris’ recent output speaks directly to that — not nostalgic, not trying to “go ambient,” but genuinely searching for emotion in sonic sounds.

“Vicious Charm will be a label where anything goes—whatever music we just can’t stop listening to—that you want to tell everyone about… that’s what we shall put out.”

In an age obsessed with algorithmic engagement and sonic maximalism, Damian’s approach feels pretty radical. His records welcome quiet. Stretching time. Favoring mistakes over perfection. And in doing so, they allow us room to breathe, something increasingly rare in both music and life. Damian is still remixing, still digging, still chasing that perfect drop of reverb. And while the days of Big Beat may seem like a fever dream, he has never stopped growing. From basement bombs to Balearic dubscapes, a story of maturity, growth, toward what feels right, even if it’s not what sells.

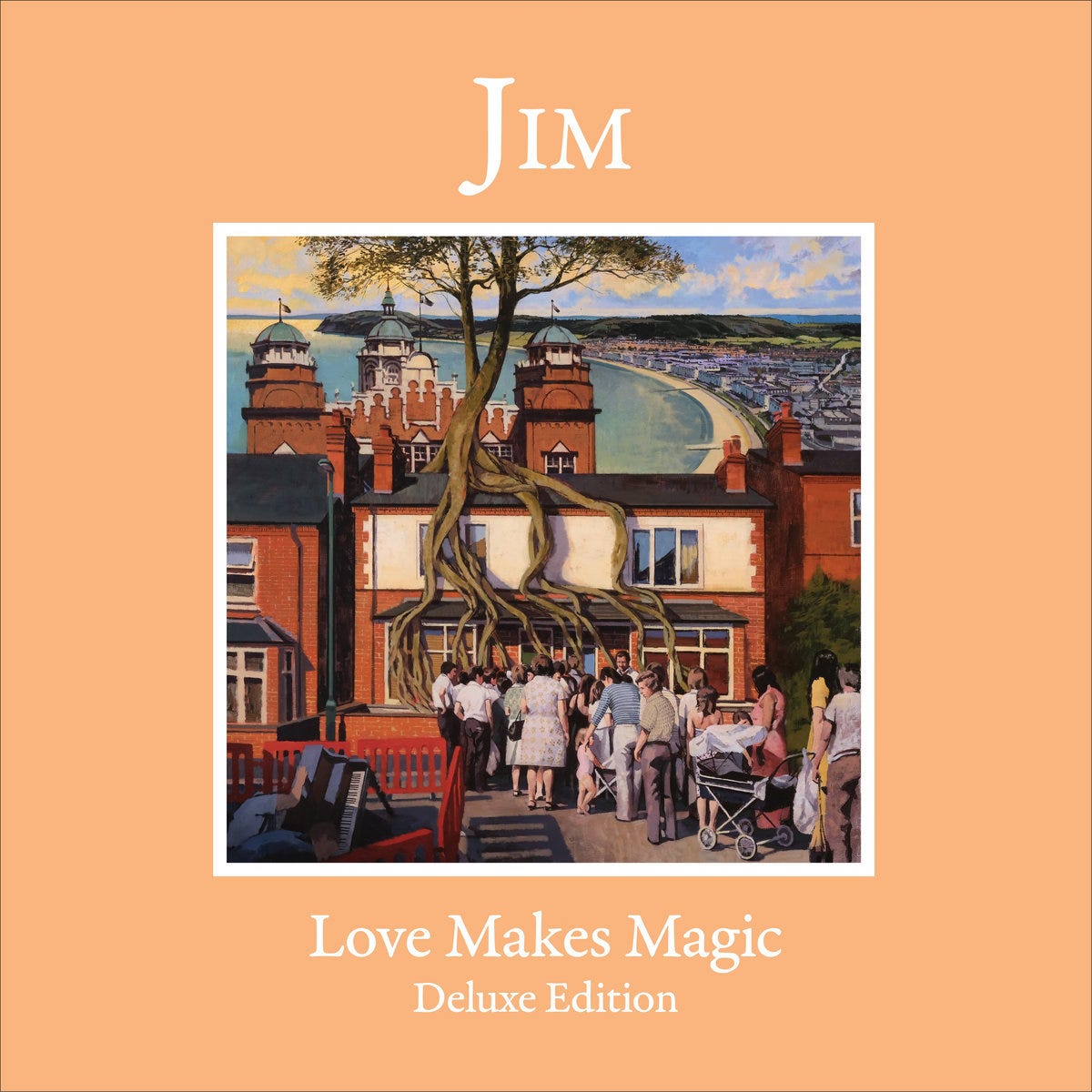

Love Makes Magic

There’s something ancient in Love Makes Magic, like sunlight spilling through stained glass, or the warm hum of a family country kitchen before breakfast. Jim’s voice, rich, close, quietly confident moves like breath through leaves. The record feels pastoral, but not in a twee, escapist way. Instead, it’s rooted. He sings of big feelings with small tools: a few chords, hand percussion, harmonies that arrive like old friends over for a pint. The title track, pulses with quiet certainty. It’s not trying to dazzle you. It’s trying to remind you of something you already knew, that love, really, is the only working magic left. The production is intimate and layered. Tape warmth, subtle synth pads, a cheap old drum machine hiding in a hedgerow. You can hear the rooms it was recorded in, space filled with rugs, houseplants, puff, incsense, chipped tea mugs half-full of cold tea. It carries the same feels early Iron & Wine, with a modern softness. It’s a record that holds your hand while you walk through grief, or the very ordinary mess of living. Quietly psychedelic, spiritually healing, this is folk music for the afters.

Mountain of One

This feels like a companion piece to Salvado, older, wiser, and less concerned with the club. It recalls the longform psychedelia of Fizheuer Zieheuer — but if that track was a march through the desert, this one is a slow ascent into mist. Villalobos’ genius has been to take minimalism and make it maximal in feeling. On Mountain of One, he channels that same spirit found in ambient/techno artists Deepchord, where texture is a kind of narrative. There's a nod to the dub techno lineage, à la Porter Ricks, especially in the way low-end weight and delay act like anchor. But where Porter tends toward shadowy and submerged, Mountain of One is luminous — like waking up in a temple made of Ice and tape hiss. It's not made for the dancefloor, but for long walks alone, watching fog roll in. One of those tracks that feels like it’s always been playing somewhere.

It’s tempting to look back at Skint’s catalog and see a genre’s short lifecycle burn up. But look closer, and you’ll see the shadow of someone tuned to vibrations, textures, and emotional temperatures. Big Beat was just the youthful swagger. Vicious Charm is the confident adult walk.

I made two Spotify Playlists to accompany this article for Paid Subscribers.

“It might sound like hippy bullshit but fuck it… It's perfect.”

Damian Harris

And where does all this end? Somewhere between the bass bins of Brighton basements and the fields of the South Downs. A way of being in this fucking world. A Celtic prayer, recorded with tape echo and sent spinning with a caseload of reverb.

Thanks for listening,